Normal and Abnormal Sexual Differentiation

The words, “It’s a boy” and “It’s a girl” can be heard every hour of every day all around the world. But how distressing it must be when the birth attendants are unable to make such a clear pronouncement? Ambiguous genitalia occurs in about one in every 2,000 births, is usually unanticipated and can be a difficult experience for all concerned. What causes ambiguous genitalia? What can be done to correct it? The following information has been developed to answer such questions.

What happens under normal conditions?

The development of the human embryo into a male or female is a complex process that is both dynamic and sequential. Interference with this highly ordered process at any step could result in abnormal sexual differentiation.

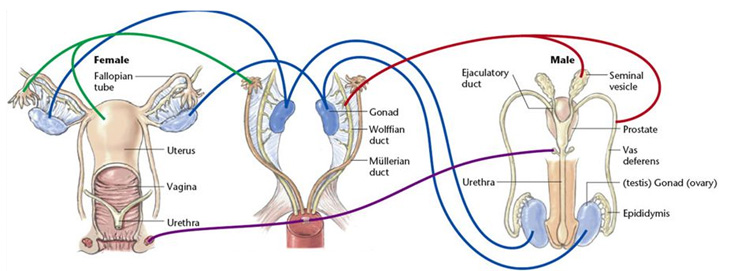

At the moment of conception, the mother imparts an X (female) chromosome and the father an X or Y (male) chromosome, creating either an XX (female) or XY (male) embryo. Despite this immediate definition of genetic sex, male and female embryos are identical with respect to internal and external genitalia until the seventh or eighth week of pregnancy. In these early weeks, embryos have two gonads – undefined organs that, during the pregnancy, will develop into testicles or ovaries based on whether the embryo carries the Y chromosome. This chromosome carries the gene responsible for testicle formation, and it is the secretion of testosterone that determines how internal and external genitalia will develop.

Young embryos at this stage also have both male and female internal genital structures. Depending on secretion of testosterone, one set of internal structures will regress, becoming either distinctly male (prostate and vas deferens) or distinctly female (uterus, fallopian tubes and vagina). It is important to note that it is the absence of the male hormones – rather than the presence of female ones – which causes the external and internal genitalia to become female. By the end of the first trimester, embryos can be recognized as having male or female external genitalia. The formation of the internal and external genitalia is called sexual differentiation.

What are some of the processes involved with sexual differentiation?

Gonadal sexual determination: In 1921, it was shown that humans have X- and Y-chromosomes. But it was not demonstrated until the 1950s that the Y chromosome specified development of the testicle.

Over the past 50 years, there has been an intense search to identify the testicle-determining gene, which, in essence, flips the developmental switch for a gonad to develop into a testicle. In 1990, Sinclair and his group discovered a small genetic sequence on the Y chromosome that they believed represented the testicle-determining factor. This gene, called SRY (for sex determining region-Y gene), has now been scientifically demonstrated to be the testicle-determining factor. There also appear to be other genes that are important in the process of sexual differentiation. They appear to act as a series of sequential switches to turn on cellular processes, resulting in development of a testicle or ovary.

Chromosomal sex determination: During the first six weeks of an embryo’s development, the cells that develop into gonads, internal ducts and external genitalia have the potential to become male or female and are therefore called “bipotential.” In the presence of SRY, the bipotential gonad develops into a testicle, which becomes apparent at six to seven weeks of development. In the absence of SRY, an ovary results.

The fetal testicle begins producing hormones at the seventh or eighth week of pregnancy but direct development of the internal ducts and subsequently, external genitalia does not take place until weeks nine to 12.

In the presence of ovaries and in the absence of testicular hormones, the internal ducts and external genitalia follow a female path of development. While the ovary has been shown to produce hormones at the eighth week of pregnancy, the role of these hormones in sexual differentiation is unclear.

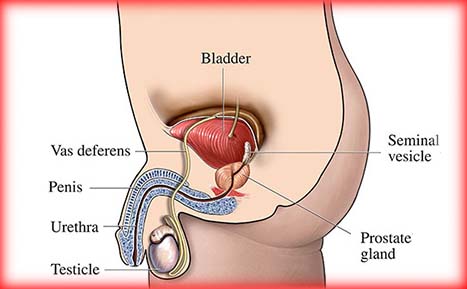

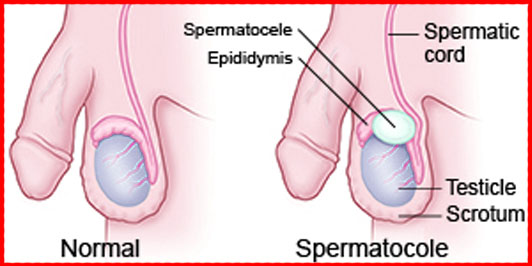

Phenotypic sexual differentiation: Before the eighth week of development, the internal reproductive ductal system is identical in the two sexes. As a result of testicular hormones, the rudimentary male ductal system develops and the female system disappears. At the tenth week of pregnancy, adjacent to the testicle, epididymis, vas deferens and seminal vesicle appear. In the female fetus in which testicular hormones are not produced, the rudimentary female internal ductal system develops and the male internal ductal system disappears. As a result, adjacent to the ovary, fallopian tubes, uterus and the upper vagina form.

The fetal tissues that develop into male or female external genitalia are also bipotential. Under the influence of testicular hormone (androgen), male external genitalia begin developing during the tenth week of pregnancy. In the third trimester, testicular hormone secretion results in growth of the penis and testicular descent. In the female fetus, in which no testicular hormone is circulating, the rudimentary tissues develop into a clitoris and labium.

What are ambiguous genitalia?

The medical term “intersex” is used to describe a number of conditions that affect the formation of the genitalia early in pregnancy, resulting in an appearance that is typical of neither a boy nor a girl.

What causes ambiguous genitalia?

The reproductive organs and genitals associated arise from the same fetal tissue. If the genetic process that causes this fetal tissue to become “male” or “female” is disrupted, ambiguous genitalia can develop. Even if genetic sexual determination occurs uneventfully, hormonal sexual differentiation can be disrupted. For example, a baby could still have ambiguous genitalia due to inadequate or overabundant levels of the male sex hormone testosterone. The precise underlying cause can usually be determined so that a recommendation can be made as to the appropriate gender in which to raise the baby.

How is ambiguous genitalia classified?

Ambiguous genitalia ranges in degree of severity but the most common variations include:

True hermaphroditism: Children who have both male and female genitalia and internal reproductive organs.

Gonadal dysgenesis: Children who have internal organs that are primarily female, external genitals that may vary between normal female and normal male and an underdeveloped gonad.

Psuedohermaphroditism: Children who have questionable external genitalia but have only one gender’s internal reproductive organs. For instance, a person may have a uterus, fallopian tubes and vagina but not a clearly defined clitoris and labia.

Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH): Females with CAH are born with an enlarged clitoris and normal internal reproductive tract structures. Males have normal genitals at birth. CAH causes abnormal growth for both sexes; patients will be tall as children and short as adults. Females develop male characteristics and males experience premature sexual development.

How can the exact cause be identified?

The necessary investigations to determine the underlying cause of your baby’s problem include various blood tests and an ultrasound of the abdomen and pelvic area. Investigation will also include a genitogram, which is a special X-ray test. During this test, a radiologist inserts a small catheter into the urethral opening and injects a contrast dye that will determine if a vagina exists. In addition, it may sometimes be necessary to take a sample of tissue from the gonads for examination under the microscope to be certain of their nature.

What are some recommended treatments?

Surgery will also be offered so that the genitalia can look normal, like those of any other boy or girl. Nowadays, operations to correct masculinized female genitalia, when carried out by an experienced surgeon, are remarkably successful resulting in an appearance, that is indistinguishable from that of a normal girl. Surgery, though, is not always necessary, particularly among girls with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) who are only slightly masculinized, as the clitoris often becomes less prominent as treatment to correct the underlying hormonal imbalance begins to take effect. A concealed vagina, however, will invariably need some surgery to bring its opening out onto the surface. When the vagina is hidden just under the skin, this is often carried out shortly after birth, although when it lies deeper in the pelvis, it is best delayed until one or two years of age.

Surgeons are becoming increasingly aware that it is important for girls to retain normal sexual sensation after genital surgery. Therefore, in cases in which the clitoris is greatly enlarged, necessitating removal of a portion of the erectile bodies to improve appearance, great care is taken to avoid injury to the sensory nerves and to preserve the blood supply to the glans. It must be acknowledged, however, that there are few long-term follow-up studies to determine to what extent surgeons have been successful in achieving these objectives. It is, however, well recognized that, after vaginal surgery, there is a tendency for the newly created opening to narrow down. This sometimes necessitates further surgery, although more often, simple dilatations begun during the teenage years prior to any sexual activity are all that is required.

Surgery for boys is usually successful in converting an ambiguous penis, which is usually tethered down with the urethral opening set well back towards the scrotum, into one that looks remarkably normal. Any separation of the scrotal sacs will usually be corrected at the same time. The operation is usually carried out between six months and 18 months of age and is frequently accomplished in one stage as an outpatient procedure. Once healed, the penis continues to grow in pace with the child’s physical development, and further surgery is rarely needed. The structures necessary for sensation and erectile function are undisturbed by the surgery.

In boys who harbor a uterus, this is usually removed when the diagnostic laparoscopy or laparotomy is carried out. An associated vagina, if large, will usually be removed at the same time, although rudimentary structures can be left undisturbed in the knowledge that their presence is unlikely to cause any problem.

Frequently asked questions:

Will my child be able to produce children as an adult?

Babies with congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) or pseudohermaphroditism can be regarded as potentially fertile once the underlying hormonal imbalance is corrected. Babies with other conditions must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis. For example, those with true hermaphroditism also have the potential to be fertile. Other girls, for example those with testicular dysgenesis, may have had their gonads removed because of the risk of tumor development, yet a well-developed uterus will have been left in place so it can potentially nurture an implanted embryo conceived in the laboratory using modern assisted reproductive techniques. Boys having at least one testicle, which on biopsy is shown to be normal, have the potential to be fertile, although this is by no means certain.

Will my baby have psychological problems down the road, particularly with regard to sexual preferences or gender identity?

Among girls whose external genitalia were only slightly masculinized at birth or who have undergone modern feminizing surgery, experts have no reason to think they will later be displeased by the appearance of their genitalia. Similarly, provided the caliber of the vagina is checked prior to the onset of sexual activity and adjusted, if necessary, such girls should be able to have intercourse without any problem.

Among boys, the correction of even severe hypospadias should not compromise their ability to have satisfactory intercourse. Ejaculation, however, may be rather less forceful than normal, particularly when it was necessary to reconstruct much of the penile urethra.

We are on rather less certain ground when it comes to the long-term psychosexual outcomes, particularly with regard to gender identity. In the past few years, we have become increasingly aware that testosterone, the hormone responsible for producing masculinization of the external genitalia, may potentially have had an effect on the developing brain, programming such an individual to think along male lines and, perhaps, even develop a male gender identity. This clearly has important implications when the decision is made to raise any masculinized infant as a girl.

Hello there, I do think your web site could be

having web browser compatibility issues. When I take a look at your site

in Safari, it looks fine but when opening in I.E., it’s got some overlapping issues.

I just wanted to provide you with a quick heads up! Besides that, excellent website!

Ahaa, its pleasant dialogue concerning this post here at this webpage, I have read all that, so now me also commenting here.

Hello buddy is see you aren’t making money on you website.

You can earn a lot using one simple method, search on youtube:

how to make money online reselling seoclerks