Before birth, there is a connection between the bellybutton and the bladder. This connection, called the urachus, normally disappears before birth. But what happens if part of the urachus remains after birth? Read on to learn more about what problems can arise.

What happens under normal conditions?

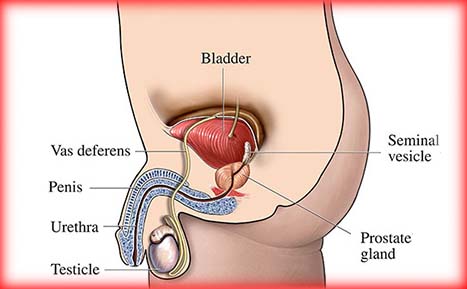

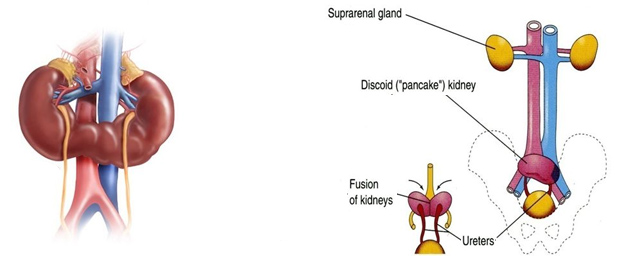

The bladder, located in the lower abdomen, is formed from structures located in the lower half of the developing fetus that are directly connected to the umbilical cord. After the first few weeks of gestation, this thick pathway to and from the placenta contains blood vessels, a merged channel to the future intestine and a tubular structure called the allantois. The internal part of the allantois is connected to the top of the developing bladder, and in ordinary circumstances, collapses and becomes a cord-like structure called the urachus. The formation and regression of this connection from the top of the bladder to the bellybutton are completed by the middle of the second trimester of pregnancy (approximately 20 weeks).

Although the urachus is easily seen by a surgeon whenever an operation inside the abdomen or around the bladder is performed, it is a remnant of development that serves no further purpose but can be a source of specific health problems. Such problems are rare and usually seen in childhood, but occasionally can be seen for the first time in adults.

What are the symptoms of urachal abnormalities?

Because this remnant of early development is found between the bellybutton and the top of the bladder, diseases of the urachus can appear anywhere in that space. In newborns and infants, persistent drainage or “wetness” of the bellybutton can be a sign of a urachal problem. However, the most common detectable problem at the bellybutton is a granuloma, a reddened area that is present because the base of the umbilical cord stump did not heal properly.

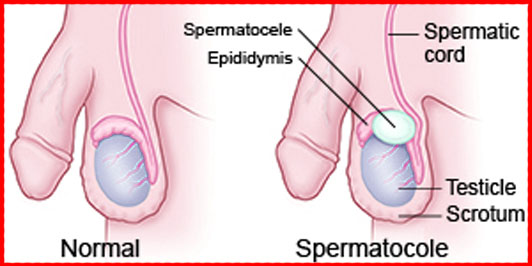

Urachal abnormalities can also be seen without persistent umbilical drainage — 35 percent of urachal problems are manifestations of an enclosed urachal cyst or infected urachal cyst (abscess). This type of problem is seen more often in older children and adults. Instead of visible bellybutton drainage, the symptoms of such a cyst consist of lower abdominal pain, fever, a lump that can be felt, pain with urination, urinary tract infection or hematuria.

How are urachal abnormalities treated?

A umbilical granuloma is usually treated by chemical cauterization in the office of the primary care provider. The condition is a superficial abdominal wall problem that heals after treatment and has no long-term implications; it is not caused by a urachal problem.

In contrast to the simple granuloma, persistent umbilical wetness needs to be further evaluated. Approximately 65 percent of all urachal problems appear as a sinus or drainage opening at the bellybutton. Most of those are not connected all the way to the bladder, but a small percentage represent an open pathway from the bladder to bellybutton, called a patent urachus. The drainage can be analyzed for urea and creatinine levels, which would be high if the fluid was primarily made of urine from a bladder connection instead of inflammatory tissue fluid. There can be associated redness from the drainage itself. Skin infection – indicated by tenderness, fever or spreading redness of the surrounding skin – can occur and requires prompt antibiotic treatment and possible hospitalization. This is called omphalitis and can be caused by bacteria that have become involved with a urachal sinus or the other embryologic structure in the bellybutton that was once connected to the intestinal system and might also be persistent. Once inflammation is controlled, the nature and extent of an opening at the bellybutton can be determined by a sinogram. This involves placing a small tube into the sinus opening and allowing contrast material to flow in while taking X-rays to determine the direction and extent of the channel. If the channel follows the expected pathway toward the top of the bladder, the diagnosis is urachal sinus. Treatment should be directed toward complete surgical removal of the urachus and all of its connections, including a small amount of the top of the bladder. Leaving any portion of the structure allows for the possible development of a future malignancy. Less than 1 percent of all bladder malignancies occur in the urachus, but once the urachus has become a potential problem, it should be removed.

When there is no draining sinus to investigate, an ultrasound of the lower abdomen will show the typical findings of a fluid-filled, enclosed lump in the location of the urachus. In an adult, where the rare possibility of malignancy could be present, an abdominal and pelvic CT scan might be helpful. Again, complete removal of the urachus is important. Simple needle or other drainage of the cyst will result in recurrence in at least one-third of patients, since the linings and structures are still present. About 80 percent of infected cysts are populated by staphylococcus aureus, and one-third contain multiple types of bacteria. Almost all the time, such an infected cyst stays confined to its predetermined anatomical location; rarely, an infected cyst can drain into the peritoneal cavity and present with additional signs of peritonitis and febrile illness.

Therefore, most urachal problems can be characterized by the physical examination and a sinogram or ultrasound. Sometimes a combination of these is needed, and occasionally it is useful to obtain a voiding cystourethrogram. This is done when the draining urachus is associated with outlet obstruction of the bladder, which would also need to be treated. This possibility is usually determined by the age, gender and physical examination of the patient. There are also situations where a direct look inside the bladder (cystoscopy) can add a bit more information to the diagnostic picture, but most urologists recommend that the basic course of action be determined by the previously described approach.

What can be expected after treatment for urachal abnormalities?

After complete surgical removal of a troublesome urachus with no immediate postoperative problems, there should be no further issues and no need for follow-up or evaluation on a regular basis.

Frequently asked questions:

Besides the problems that have already been outlined, are there other diseases that appear at the bellybutton?

As you might expect, there have been rare reports of other inflammatory problems involving the structures that are contained in the umbilical cord. These include infections of the remnant blood vessels. In addition, the vitelline duct, which is supposed to regress in its course between the bellybutton and the small intestine, sometimes has its own remnant problems. The sinogram that is useful for identifying urachal problems will also serve to identify a likely vitelline duct problem.

Occasionally, an intra-abdominal process such as appendicitis or ovarian cyst can mimic some of the symptoms of a urachal problem.

Are urachal abnormalities hereditary?

No. There is no evidence that they are inherited.

After my baby’s umbilical cord stump came off, his bellybutton was extremely red. Is this normal or does he need immediate evaluation?

Some redness is expected after the stump falls away. Dabbing a small amount of alcohol on the site with a Q-tip twice a day will usually allow complete healing in two to three days. If the redness fails to improve or worsens, contact your primary care provider.

Desde nuestra empresa, ponemos a tu disposición nuestro equipo de

desarrolladores de apps para Android.