Andrew Wilson was always a big kid. During his 20s and 30s he kept his weight at bay by playing sport, but when his family hit a crisis and he was under pressure in his financial services job, he stacked on the weight.

“Mate, what are you doing to yourself?” his doctor asked him. Andrew was so ashamed, he did not see another medical practitioner for ten years.

The thing was, he was trying to lose weight. He watched what he ate and exercised. Still, his weight ballooned to 200 kilograms and he developed a range of health complications.

He tried many diets. He would lose ten to 20 kilograms, but then the weight would return, and more. He was always hungry; all he could think about was the next mouthful of food.

“It’s like the time I tried intermittent fasting. By the evening I’d be ravenous. I would be preparing the evening meal for my family and I would be so hungry I’d be eating the ingredients,” he says.

“Most people have a feeling of having finished a meal, but I never had that satiated feeling. And it wasn’t just physical. Mentally, I wanted more.”

Andrew is certainly not alone. Obesity affects all areas of society; in every classroom, in every shopping centre and street, people everywhere are living with excess weight or obesity.

In Australia, more than two thirds of adults and at least one quarter of children are now considered above a healthy weight. Many children are above a healthy weight before age five and, according to research, this means they’re likely to continue to be overweight throughout their lives.

People with obesity can experience serious health problems. Despite the fact it’s so commonplace, those living with obesity still tend to attract blame for their condition.

“The worst thing is the stigma,” says Andrew, who now is in his late 40s. He supports other people living with obesity through the Weight Issues Network, an organisation that addresses weight stigma.

“I remember when the parents at my son’s kindergarten didn’t want to talk to me outside the classroom. Some wouldn’t even look at me because of my size. That impacted my son, he was teased.

“We all feel compassionate about someone who has anorexia and feel there must be some mental health issue going on there. It’s the same for those of bigger sizes – there is usually a mental health component. Why don’t people look at us with compassion also?”

It’s true that most of us – including policy makers and healthcare professionals – tend to blame people for putting on weight.

But there’s increasing recognition that obesity is caused by a complex set of factors outside an individual’s control, such as illness, genetics, childhood trauma, the environment and society. In Andrew’s case, he turned to food at a very young age as a coping mechanism for physical and mental abuse.

Paediatrician Professor Louise Baur says when she trained as a medical student in the 1970s, the subject of obesity was covered in a one-hour lecture during the entire six-year course. It was also not seen as an issue concerning children.

But then something happened. From the 1980s, doctors started to see more young patients who were becoming dangerously overweight. Today, in her clinic at The Children’s Hospital at Westmead in Sydney, Professor Baur sees a succession of children with moderate to severe obesity – and it’s making them very sick.

“I never ever used to see kids in the 1980s with type 2 diabetes, now we see them every day,” says Professor Baur, who heads The Centre of Research Excellence in Translating Early Prevention of Obesity in Childhood.

“I’m seeing a lot of kids with fatty liver disease, and others with obesity-related major orthopaedic problems that mean they need major orthopaedic surgery. There’s been a rise in obstructive sleep apnoea in children, meaning we’re putting kids on CPAP machines; there are now many children with pre-diabetes and diabetes who need to be on medications.”

Obesity is no longer a first-world problem. International experts who gathered at the International Congress on Obesity in Melbourne recently heard from countries all over Asia, South America, the Pacific Islands and Africa that their populations are experiencing a pandemic of obesity.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than one billion people worldwide are living with obesity – 650 million adults, 340 million adolescents and 39 million children. This number is still increasing, and the WHO estimates that by 2025, approximately 167 million people will live with overweight or obesity and related health issues.

What’s going on? Has the whole world turned to overeating in the last 40 years? Or are there other factors at play?

The problem is that in recent decades the way we live has changed dramatically. Most people in the world are eating diets full of high-energy foods – like takeaways, chips and sugary drinks – and at the same time we’re moving less as we grow increasingly reliant on cars.

Many developing countries are now awash with ultra-processed foods and soft drinks. People are choosing instant noodles and soft drinks over vegetables and grains. At the same time, everyone is sitting much more. Think of a photo from Asia in the 1970s – everyone was on a bicycle. Today they’re on mopeds or riding in cars.

Humans aren’t meant to live in an environment like that. Our bodies are hard-wired for fat preservation. As hunter gatherers, it was the ones who carried a few extra kilograms who were able to survive famines, while the skinny people would die.

More than 100 genes have been identified that are partly responsible for obesity. Identical twins put on fat in exactly the same way, on the same parts of their bodies, even if they do not live together.

“I’d say that around 60 to 80 per cent of overweight and obesity can be attributed to genetics,” says Professor Brian Oldfield from Monash University, editor-in-chief of Obesity Reviews.

But here’s the rub. Once we start to put on weight, our biology changes to make it harder and harder to lose it again.

One study followed a group of overweight people on a low-carbohydrate diet for ten weeks. For the whole of the next year, the dieters’ hormones that control appetite and cravings for food were abnormal.

“The hormones that would normally promote hunger were exaggerated and the hormones that would promote feeling full were reduced,” Professor Oldfield says.

Another study followed contestants from the TV programme The Biggest Loser in the US. While all of them achieved profound weight loss, for years after the show they didn’t use as many kilojoules as everyone else when they exercised. The contestants’ bodies were desperately trying to adapt to weight loss and bring their weight back to the starting point. The result? All the contestants put on most of the weight they’d lost.

Worryingly, these biological problems can start even before we’re born. For example, mothers who eat high-fat diets during pregnancy predispose their infants to prefer highfat foods, says Professor Oldfield. As a society, we’re setting up our children to get fatter and fatter.

Developing obesity can change our relationship with food, too. Every time we eat, our brain is flooded with feel-good hormones. These hormones become dysregulated in people with obesity. For some people, eating can become more like taking a drug – something they are compelled to do to get the next hit.

“It’s different to a person who is slightly overweight and who can potentially just cut down and lose a few kilograms,” says Andrew Wilson. “If you are bigger, after that initial loss of ten to 15 kilograms, your body just slows down your metabolism and makes you hungry.”

For people who are permanently hungry, our environment makes it next to impossible to make healthy choices.

Obesity Policy Coalition executive manager Jane Martin says much of what we eat is being shaped by multinational companies, who have extraordinary power and influence in many countries.

Like the tobacco industry before it, the food and drink industry is promoting unhealthy ultra-processed foods as being healthy, aligned with happiness, or linked to sporting success.

“A lot of what is on supermarket shelves is highly processed. It’s heavily marketed and is readily available and very well priced. Our social norms have been shaped to make these products a normal part of our diet, for example through marketing, which creates a strong desire for those products,” says Martin.

“You see people in the supermarket trying to decipher the nutrition panel but they can’t. What individuals can do is relatively limited because it’s just so difficult to have a healthy diet these days.”

Obesity has serious consequences for health. It’s a risk factor for a range of chronic diseases, including heart disease, cancer, asthma, diabetes and liver and kidney disease.

Most of the world’s population now lives in countries where overweight and obesity kills more people than being underweight. Thirteen per cent of the world’s adult population had obesity in 2016 – nearly three times the number than in 1975.

‘Malnutrition’ – or ‘poor nutrition’ – used to conjure up images of children in developing countries without enough food to eat. The problem in most countries is that while highfat, high-sugar, high-salt, high-kilojoule processed foods are cheap and filling, these foods are to blame for poor nutrition, as they don’t contain the nutrients people need for good health. That means the same person can be overweight and undernourished at the same time.

“Globally, there are more people who are obese than underweight – this occurs in every region except parts of sub-Saharan Africa and Asia,” says WHO spokesperson Dr Margaret Harris.

“Many low- and middle-income countries are now facing a ‘double burden’ of malnutrition. They continue to deal with the problems of infectious diseases and undernutrition, while they are also experiencing a rapid upsurge in risk factors for longterm diseases, such as obesity and overweight, particularly in cities. It’s not uncommon to find undernutrition and obesity co-existing within the same country, the same community and even the same household.”

The problem is getting worse. The explosion of obesity that started from the 1980s has gathered pace since the COVID-19 pandemic. Countries everywhere are reporting solid evidence that their populations put on weight during lockdowns, and that weight has not yet come off. Ironically, people who have obesity are also more likely to die or become very unwell if they catch an infectious disease or have surgery. During COVID, high body mass index was one of the major risk factors for severe disease and death.

That’s because obesity causes chronic inflammation, subtly changing the immune system. Extra body fat can make it harder to move the airway and the chest wall, putting people with obesity at greater risk of breathing problems.

“Hospital systems all over the world are really struggling at the moment under the double burden of COVID and obesity-related health problems,” Professor Baur says.

The good news is, there’s plenty that can be done. Telling people to eat less and exercise more has not worked – but, like many other health conditions, obesity can be addressed with healthier environments and evidence-based treatments.

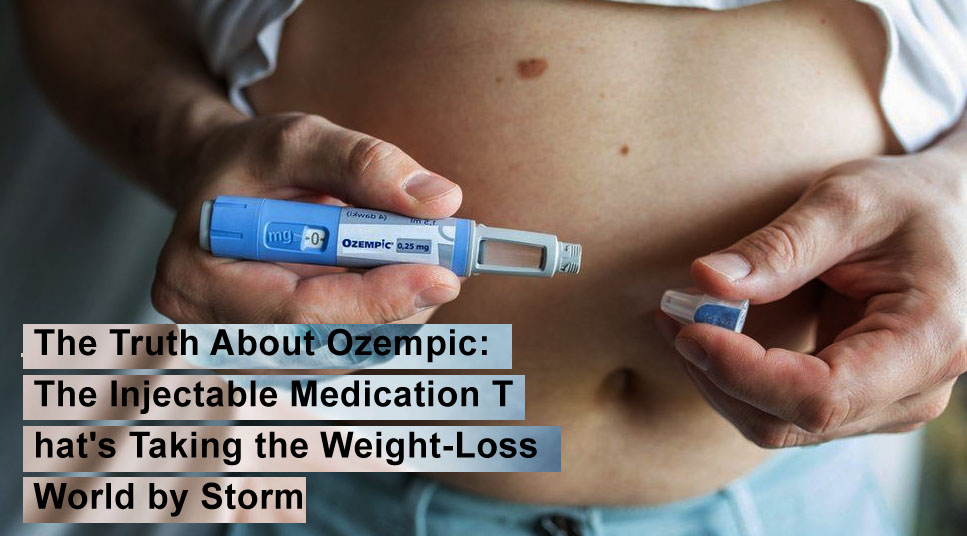

While the main treatment for obesity is still bariatric surgery, new medications are available that can achieve similar results. Soon, obesity experts predict, obesity will be commonly treated with regular injections or pills, just like diabetes or high blood pressure.

There are also ways of improving the environments we live in. Governments can make it easier for us to do physical activity, for example, by planning towns with green open spaces, and providing safe footpaths and plenty of public transport to lure us away from our cars. The food supply can be improved by regulating marketing of unhealthy foods, especially to children.

One solution that has proven very successful overseas in reducing sugar consumption is to introduce a tax on sugary drinks. In the UK, for example, a health levy on drinks containing more than eight grams of sugar per 100 millilitres saw the population reduce the amount of sugary drinks that they bought even before the tax came into force.

“The price of traditional soft drinks went up and people drank less of them. The companies’ profits didn’t decline but much less sugar was consumed by the population,” says Jane Martin.

Professor Baur, who is also President of the World Obesity Federation, says perhaps the most important thing is for us all to be a little kinder to the people we all know living with overweight and obesity. “Obesity is a biological disease, not a behaviour. It’s not something over which an individual has sole control. It’s a problem that the whole system needs to address.”

Andrew finally summoned the courage to go to an obesity treatment clinic. By this time, his blood pressure was through the roof. “The clinician said if it wasn’t for the fact I was walking around she would have admitted me to the ICU.”

Since then, with the help of a team including an endocrinologist, dietitian, physiologist and psychologist, as well as weight loss surgery, he has lost more than 50 kilograms and is still losing.

“My medication has more than halved, my breathing has improved and I’m active. My mental health is also a lot better,” he says.