PSA screening for prostate cancer has become standard for older men. Now some experts say the test leads to too many serious side effects to continue to be safely used.

Last year 30 million men in America had a PSA test, a routine screening for prostate cancer for men over 50. The test is considered the most effective way to detect the disease, which kills 34,000 men each year. But last fall the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force kicked off one of medicine’s most contentious debates when it drafted a recommendation that healthy men should no longer get the test. “This is not what anyone had hoped for,” says task force chair Dr. Virginia Moyer of the panel’s decision, “but we cannot recommend using a test that does not work and causes harm just because it’s the only test available.”

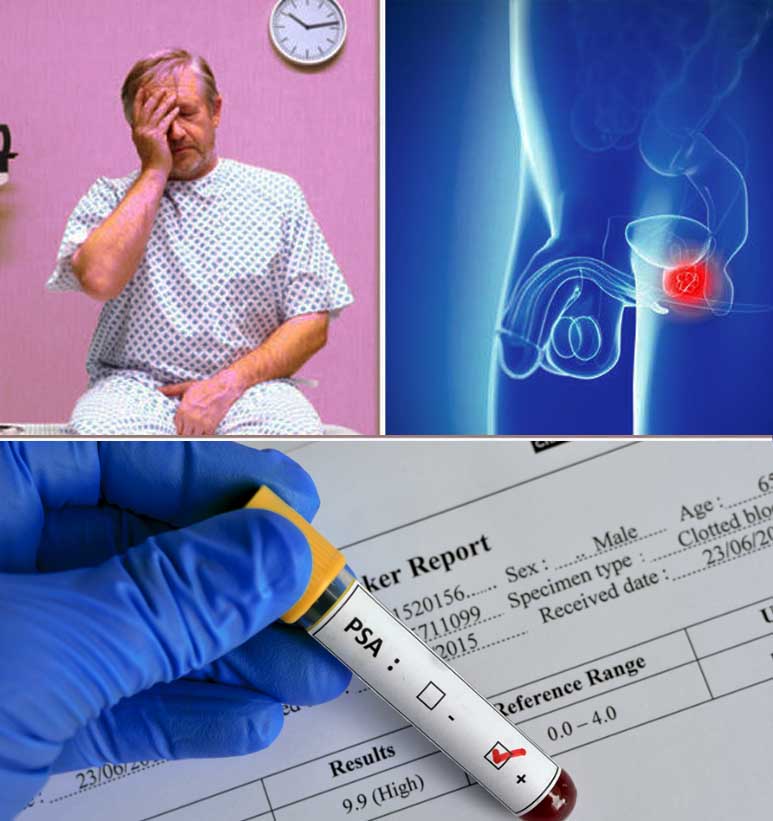

How could something designed to detect cancer be harmful? The answer lies in the details of the test itself. PSA, or prostate-specific antigen, is a protein produced by the prostate gland that, at high levels, may — but does not always — indicate the presence of cancer. High PSA levels can also be caused by an infection or an enlarged prostate, so an elevated reading doesn’t always reflect cancer. Still, many men who are told they have a high level of PSA will opt for a biopsy — a procedure in which a needle is used to remove small samples of the gland to be tested for cancerous cells — which can cause pain, bleeding, and an increased risk of antibiotic-resistant infection. If a biopsy finds cancer, nearly 90 percent of men will undergo radiation, surgery, or androgen deprivation therapy, all of which can lead to impotence and/or incontinence. Additionally, a single PSA test can’t distinguish between the common type of prostate cancer, which grows so slowly that it’s rarely fatal, and the aggressive form, which can kill men within five years. What the task force is saying, in essence, is that the treatments often prompted by PSA screening may be more harmful than the disease itself.

Despite these facts, the task force’s recommendation against PSA testing has ignited a fiery debate between those who support the panel’s conclusion and the scores of patients and doctors who credit the test with saving lives. Former New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani, baseball’s Joe Torre, and golf’s Arnold Palmer, all of whom were successfully treated for prostate cancer after test results showed an elevated level of PSA, have criticized the panel’s decision. “Without the indication that it was there, I might still be walking around with cancer — or I might not be walking at all,” says Palmer. “In my experience, PSA screening works.” Former Florida State University football coach Bobby Bowden also was diagnosed with prostate cancer after a routine PSA test. “When you have cancer, you’ll do anything to get it fixed,” he says. Four years after receiving radiation, Bowden is cancer-free and credits the PSA with saving his life.

A number of doctors agree, arguing that though the data may not always be analyzed correctly, a PSA test is still the best way to find the disease before it becomes problematic. (Most types of prostate cancer are 100 percent treatable when detected early.) “We have fallen really short in interpreting and applying PSA data,” says Dr. Robert Mordkin, chief of urology at Virginia Hospital Center, “but that’s no reason to go back to the dark ages of pre-PSA.” He points out that, though prostate cancer is the second-most fatal cancer in men, deaths from the disease have fallen by a third since 1992 — a statistic he credits to early detection through screening. “It’s cavalier and dangerous to make these broad, sweeping statements that men shouldn’t get PSA tests,” he adds. “Not many males walk into their doctor’s office and say, ‘Hey, it’s time for my blood test.’ The task force’s recommendation just gives men one more excuse to avoid their health care.” Before the task force’s announcement, most medical organizations recommended that men receive their first PSA test at 50, and then get annual screenings each subsequent year.

One of the main problems with PSA screening, though, is that a high number doesn’t always mean that a man has cancer, while a low one doesn’t always indicate that he’s cancer-free. The American Cancer Society reports that nearly 75 percent of men who receive a borderline PSA test end up with a negative biopsy. Dr. Len Lichtenfeld, deputy chief medical officer for the American Cancer Society, tested positive for elevated levels of PSA after 10 years of routine screening. Lichtenfeld, knowing the risks involved with a biopsy and the test’s potential for false positives, suspected that he might have an enlarged prostate or a prostate infection instead. He took antibiotics and got retested; his levels had dropped.

Lichtenfeld’s experience further exposes the flaw in the blood test: The numbers produced by a PSA test are not conclusive. It was once believed that PSA readings below 4 nanograms per milliliter were normal, but a recent study now shows that cancer can be present at lower levels, too, causing the National Cancer Institute to state that there is no normal PSA number. “Men dutifully get their blood tested every year, get poked and probed, and for what?” says Lichtenfeld. “I’m not sure the PSA test is any more than a random walk in the park.”

When professor Richard Ablin discovered prostate-specific antigen in 1970, he intended it to be used as a tool to find cancer in a patient after a malignant prostate was removed — he didn’t expect that it would be used to detect the disease in men with no history of cancer. But doctors quickly adopted the PSA test and began including it in patients’ routine blood work, in lieu of the traditional detection practice: manual rectal exams. These are sometimes still performed, but usually detect only cancer large enough to be considered advanced. Since the FDA approved the PSA test in 1986, prostate cancer has become the second-most commonly detected cancer in men, but Ablin contends the statistic is misleading. Most men are diagnosed after 70, and because it takes a period of years to die from untreated types of slow-growing prostate cancer, chances are that the majority of afflicted older men will die from another ailment. “PSA testing has been a hugely expensive public health disaster,” Ablin says. “More than 1 million men have been overdiagnosed and treated for prostate cancer.”

Detecting prostate cancer

Overall health status, and not age alone, is important when making decisions about screening.

The discussion about screening should occur

- At age 50 for men at average risk of prostate cancer and are expected to live at least 10 more years.

- At age 45 for men at high risk of developing prostate cancer (African Americans and men who have a first-degree relative (father, brother, or son) diagnosed with prostate cancer at an early age (younger than age 65)).

- At age 40 for men at even higher risk (those with several first-degree relatives who had prostate cancer at an early age).

- Those men who want to be screened should be tested with the prostate specific antigen (PSA) blood test.The digital rectal exam (DRE) may also be done as a part of screening.

- Men who choose to be tested and have a PSA < 2.5 ng/ml, may only need to be retested every 2 years.

- Screening should be done yearly for men whose PSA level is 2.5 ng/ml or higher.

- The exact cause of prostate cancer being unknown it is not possible to prevent most cases of the disease.The prognosis and treatment options depend on the stage of the disease, age and health of the individual, whether it is a newly diagnosed or a recurred problem, Gleason score and PSA levels.

Man gets rid of prostate over cancer risk

The 53-Yr-Old Too Had A Faulty Gene Like Angelina Jolie, Who Removed Her Breasts

A 53-year-old British businessman has become the first man in the world to have his prostate gland removed due to a ‘faulty’ gene that put him at an increased risk of developing cancer. The man, who has family members who have suffered from breast or prostate cancer, discovered he was a carrier of the BRCA2 gene after he was asked to take part in a genetic trial at the Institute of Cancer Research (ICR) in London.

The BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes have long been linked to an aggressive form of breast cancer. Recently, actress Angelina Jolie announced she had had a double mastectomy to lower her risk of getting breast cancer after testing positive for the BRCA1 gene.

Research has also linked the genes to a fast-moving and lethal form of prostate cancer. The prostate gland is the walnutsized organ that is wrapped around the urethra and is responsible for seminal fluid production in men.

Doctors were at first reluctant when the London-based man, who is married with children, asked to have his prostate gland removed. Removal of the gland can have serious consequences. It can leave the patient infertile and also lead to permanent incontinence and sexual dysfunction.

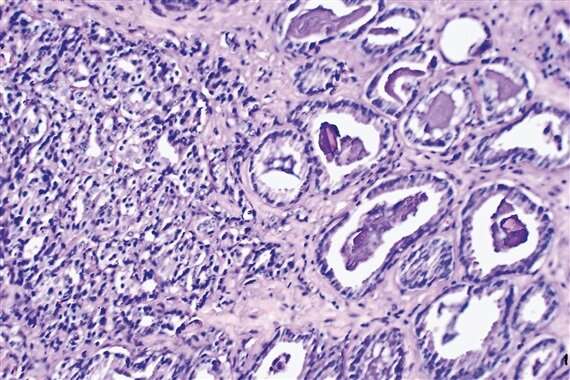

The standard prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening test conducted on the patient, which is used to detect raised levels of a protein associated with prostate cancer, did not show any abnormality. Doctors were finally persuaded to operate when a tissue sample taken from the gland showed up microscopic malignant changes.

However, the surgeon, Roger Kirby, said even then he would not have operated if the man had not been carrying the BRCA2 gene. “The relatively low level of cancerous cells we found in this man’s prostate before the operation would these days not prompt immediate surgery to remove the gland, but given what we now know about RCA2, it was the right thing to do for this patient,” said Kirby.

The experts at ICR examined the prostate gland after surgery and found a considerable level of undetected cancer.

Pancreatic ‘juices’ can help detect cancer

Scientists have developed a promising method to distinguish between pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis — two disorders that are difficult to tell apart. A molecular marker obtained from pancreatic “juices” can identify almost all cases of pancreatic cancer, researchers at Mayo Clinic, Florida, have found. Pancreatic cancer and chronic pancreatitis both produce the same symptoms in the pancreas, such as inflammation. The researchers found that the altered gene CD1D was present in the pancreatic juices of 75% of patients later diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, but was present in only 9% of patients with chronic pancreatitis.